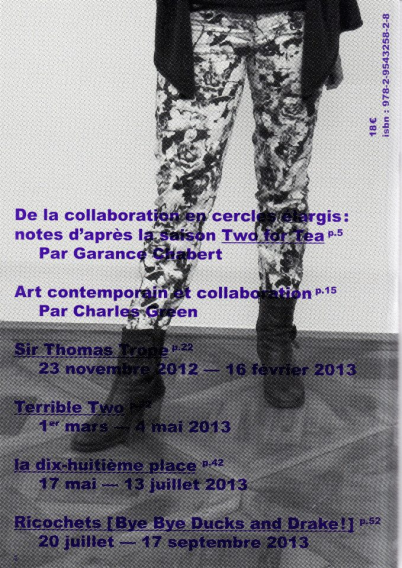

Philippe and Aimée

Jill Gasparina

I remember a comic strip divided into four frames, its pastel colours depicting two mountains conversing over the expanse of the valley that lay between them. Their dialogue was sparse, but it stretched out over a long duration. From one frame to the next, the mountains’ outlines remained the same, but the landscape changed in every one. In the first picture, it was replete with ferns. In the second one, dinosaurs roamed the land. In the third, a city had been built. In the last frame, only trees could be seen. Each frame also included a line from their dialogue. The first mountain asks how its friend is doing. How are you? The second one answers at its own mountain’s rhythm. Fine, thanks. How about you? Silence – 65 million years go by. In the fourth frame, humanity, which appeared in the previous panel, has disappeared, and the mountains doesn’t notice a thing. Fine, thanks.

Philippe faces west, Aimée faces north. Philippe is a private monument. Aimée is public art. Granted, the time of public space is not the time of mountains. But it is much longer than the time of the women and men who move through the city. Therefore, the dialogue between Philippe and Aimée will seem slow-paced to our mortal ears. It has barely begun.

Philippe still looks good. He was the son of an Annemasse butcher. He died young. As the story goes, his father had the boy’s name painted under the roof of a building he built in the 1980s to honour his memory. Philippe overlooks the park and the streets that run along it to the north and east. From his time as a human, Philippe retains a sober, brown-on-ochre look, he is tall, his sunken i-dots are retro, evoking pop art.

Colourful paintings once ran across some of the city’s walls. Vêtements Santi. Stations-services SOCAL. Mercerie Bonneterie J. Dupraz, maison de gros. Vit’ Blanc. Bijouterie Juvet. Les Galeries annemassiennes. They were still visible at the end of the 2000s, but now they have almost all disappeared. Therefore, the people who love Philippe fear for his existence.

For almost 40 years now, he has been monologuing. He calls out to those who enter the city through the rue du Parc. No one ever answers. He has witnessed the landscape’s various transformations. An art centre opening, a school being built, the park’s renovation, stores opening, closing, opening, closing, opening. The ebb and flow of construction sites and planning permissions. Queues in front of the welfare office. Le Faillitaire, a shop selling stocks from bankrupt companies, going bankrupt itself. Motorcycles. Bikes. Electric bikes. The din of cars. The brand-new tram reaching the city centre. Buildings illuminated by the evening sun. The bandstand at night, deserted. Humans going to Geneva every morning and coming back at the end of the day. Children, women, strollers and scooters flooding the park at the crack of dawn. The joyful end of the school day. Unhurried Philip has watched it all from his vantage point. Lately, the sound of worms in the park’s compost bins has started drowning out the sound of jackhammers and trains.

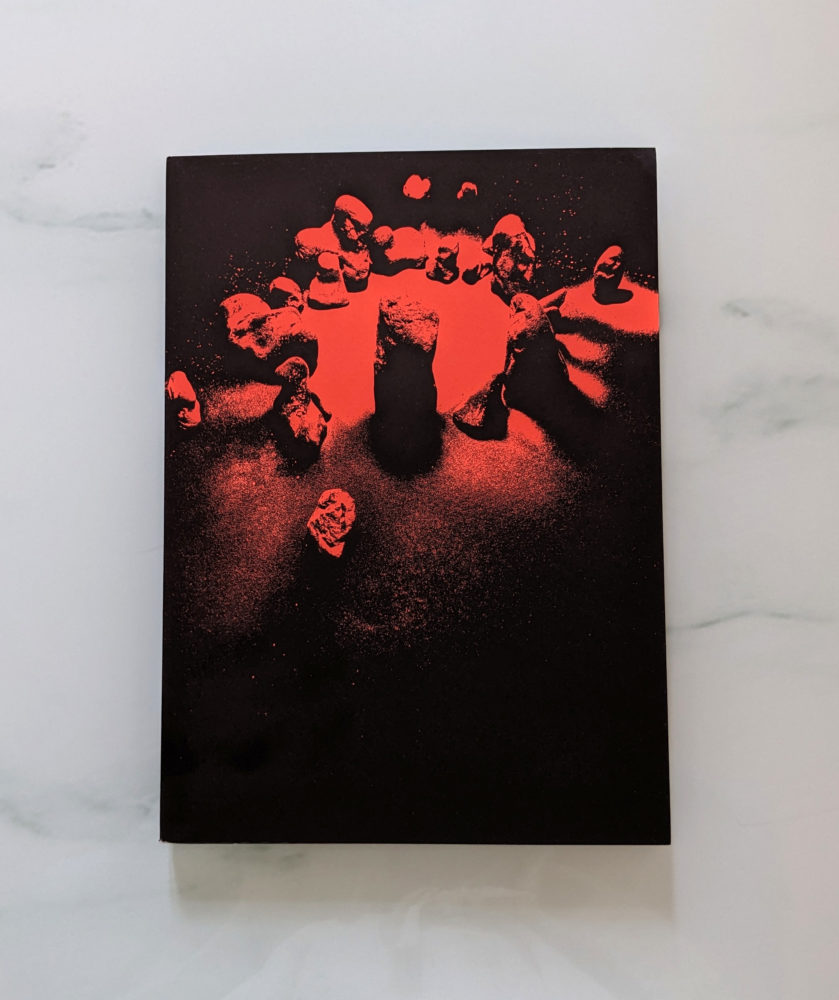

Aimée was born in 1925. She arrived in the Parc Montessuit in 2021, a long time after her death – seventeen years later to be precise, the age she was when she started helping Jewish children and Resistance fighters cross the border into Switzerland, like Mila Racine and Marianne Cohn did.

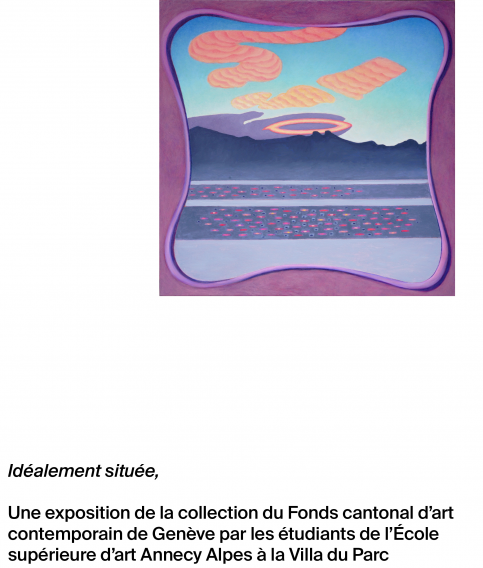

Aimée is made of various tones of blue, sprayed onto the white background of the Villa du Parc’s northern façade, where they blend more or less intensely. Her body is shaped by two large lower-case letters and an accent, nestled between the two small windows on the top floor. Aimée is a dynamic and brave giant. Her presence is impossible to ignore. She carries with her the vivid memory of the war, proclaiming the solidarity of women.

People come out of shops and walk through the park, their arms full of parcels, frozen food and fresh vegetables. Deprived men and women go by. Aimée contemplates the life of the city. In the springtime, the sequoia and cedars grow. Birds nest and hatch. Bats return, along with foxes, hedgehogs, rabbits and yellow-bellied toads. The winters are harsh, but they are not as bad as they used to be. There is a water problem.

Aimée and Philippe might have crossed paths during their lifetime, on either side of the border. But if this were the case, to my knowledge, their meeting has not been documented. I have no idea what their age difference was exactly, although I am almost certain that Philip was much younger.

Their territory consists of the continuous set of points from which they are visible, imaginable, discussed and remembered, where their names are said and written, printed and stored. Philippe and Aimée cannot speak but they generate perceptions, emotions and thoughts. Their encounter at the heart of the park is a troubled one. They cannot meet at the bandstand. Their love is lived out on pedestrian streets, rose gardens and well-kept lawns. Philippe and Aimée have all the time in the world.

NB:

I know nothing more about Philippe C. than what appears in this essay.

Aimée Stitelmann (1925-2004), was a communist and antifascist who helped “Jewish children and members of the Resistance illegally cross the border from Annemasse into Switzerland. At the time, she was condemned by the Swiss authorities. She became a teacher in Geneva after the war, and in 2004 she was rehabilitated by an amnesty law voted by the Swiss Federal Council in favour of anti-Nazi militants.

Garance Chabert, “Nota Bene on Aimée”, 2021

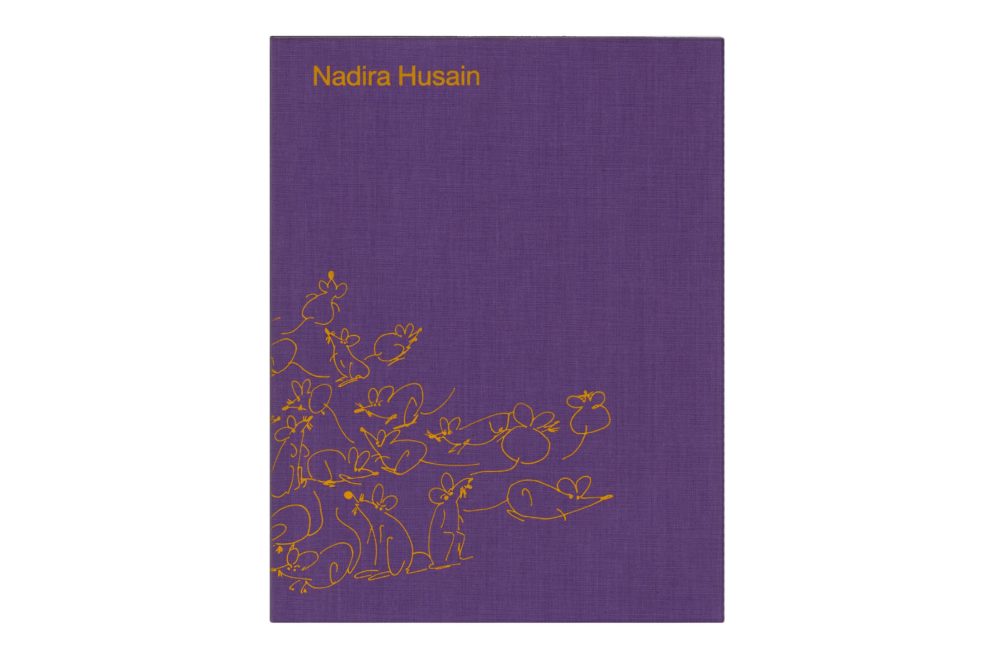

Inspired by the figure of Aimée Stitelmann, Renée Levi designed an exhibition at the Villa du Parc (Aimée) in 2021, as well as the work now visible on the centre’s façade.

I was unable to find the comic strip I mention at the beginning of the text online. It may be different from what I have described.

Renée Levi, Aimée, 2021

Crédit Aurélien Mole

![Le classisme : une introduction [extrait] - Villa du Parc](https://villaduparc.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/mg-3652-livret-72dpi-667x1000.jpg)