La sensibilité du silicium

Sylvain Menétrey

In Season 11 of American Horror Story, set in the early 1980s in New York’s serial killer-infested gay S/M scene, a phone box standing outside a leather bar sometimes rings during the night. Every now and then, a bold patron might answer the anonymous call, much to his own risk. At the Villa du Parc in Annemasse, a telephone receiver hangs down from a beveled box resembling an old-fashioned phone booth. Suspended communication, presence of an absence. One could view Niels Trannois’s exhibition In Praesentia as something of a frozen crime scene. The deadly sex phone emits nocturnal-sounding music composed by Félicia Atkinson, increasing the evanescent tension.

Elsewhere, the floor of a large room is strewn with pine needles and pine cones. A fragment of a black wrought-iron guardrail with an Art Deco herringbone pattern is placed on this Mediterranean-looking carpet, as though it has escaped from a balcony, losing a few bars in the process. A pile of wind-blown sheets of paper cling to the structure, on which the work’s title, CRACKS IN THE PLEASUREDOME, is spelled out in capital letters which fade from one sheet to the next, as the letters are progressively erased. Just like the telephone receiver used as a speaker and most of the other works shown in this exhibition (In Praesentia), the railing is covered with residue, marks and painted fingerprints, glued pieces of paper and post-it-sized thin sheets of porcelain. In the midst of all these details, the grimacing face of a stenciled or laser-engraved character appears several times throughout the show. It resembles a sigil and its most salient quality is the similarity between the upper and lower features of the character’s face, like an optical illusion taken from a Gestalt textbook. This axial symmetry is also repeated in hourglasses symbols punched into porcelain.

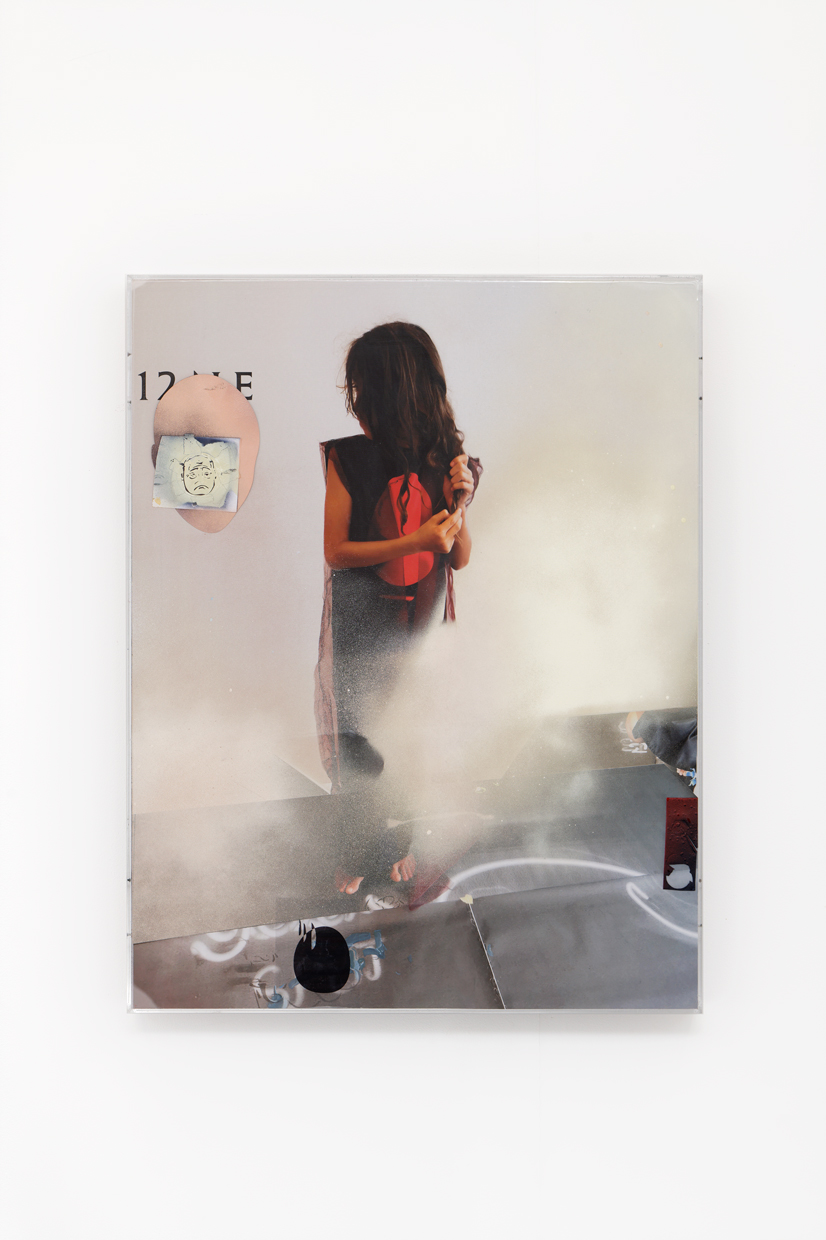

These vanities, emblems, signatures, superimpositions and overlapping miniatures call to mind the chaos of signs found in urban spaces: gunky graffiti, anti-capitalist stickers, festering posters, leaflets decomposing in the gutter, flickering neon signs and babysitting ads. This street vocabulary is combined with industrial and/or clinical materials: ornate metal beams arranged like minimalist artworks; a translucent forensic tarp that conceals or protects paintings that have been leaned against a wall and forgotten; comma-shaped anti-virus Plexiglas panels which punctuate the exhibition. But this street art has no street cred. Everything, up to the tiniest mottled bird droppings have been applied with an illuminator’s painstaking care to the railing. The telephone is delicately smeared with impressionistic blue and yellow dabs. A feather colored with shadings of blue and red, painted envelopes, a piece of cloth, a purple banknote bearing the image of the Queen of Sweden and other fragments of this still life set behind a Plexiglas panel have been carefully thought out, in their chromatic range and their layout, in order to create a tender harmony. The artist is a refined assassin who fancies embalmed living rooms.

Avant-garde art has tried to bypass the inevitable process of reification attached to the creation of art objects, in order to move closer to the pure event that life supposedly is – all in vain. This is not Niels Trannois’s territory. He sidesteps this history, embracing the fetishistic and morbid dimension of the objects whose reification he dramatizes, turning the latter into a material process of calcification. His collage-paintings are encapsulated in Plexiglas boxes as though they were fragile environments that needed to be preserved under bell jars. The swift gesture of finger-drawing on a tablet is engraved into porcelain, a material rendered inert by firing at very high temperatures, which is also used as a medium for paintings inspired by museum visits.

The enigma posed by these works lies in their lack of a stable referent: the caller is anonymous. But by digging around, one might start unearthing a string of entangled clues referencing mainstream and obscure sources. The title of a piece taken from a track by dubstep producer Shackleton, a neon seagull motif first spotted by the artist on the Dalmatian coast, an Ettore Sottsass bookend, a poster from a Berlin art off-space from the 2000s, even Beyoncé, whose name is the inspiration for an assonant poem – “be on C, beyond C”. This hyper-collage produces narrative and affective spaces inhabited by decontextualized memories. Other artists are invited, further blurring the lines: the aforementioned sound artist Félicia Atkinson; Sylvia Sleigh and her falsely naïve and homoerotic feminist paintings; the Ukrainian lamp designer Polina Moroz, and Quintana E. (an alias used by Niels Trannois for his collaboration with Jessy Razafimandimby).

One of the Plexiglas-protected scenes features an elegiac picture of a child whose face is hidden by his long hair. This, we soon learn, is the artist’s son. He is wearing a long tunic made of translucent black tulle over a T-shirt bearing a red circle. His feet are bare. The picture looks like something out of a fashion magazine or a Sofia Coppola music video. The young hippie-chic guru’s lower body is obliterated by a dash of sand-colored spray paint. He is gazing towards the righthand side of the painting, where two collaged heads are placed on top of each other. The first one is a simple paper egg-shaped cut-out with no distinguishing features. On top of it is stenciled the symmetrical-faced bald man already seen on other pieces. Through staging, stylization, erasure, doubling and signing, the personal is both over-invested and engulfed in a maelstrom of fragmented and reversible identities.

Tristan Garcia’s novel, Les Cordelettes de Browser (2012) is one of Niels Trannois’s favorite books. This metaphysical science fiction novel describes a world in which a static eternity has set in, after a seasoned astronaut sent to the edge of the universe accidentally stops the expansion of space-time. The last people on Earth live in a comfortably eventless world. The fact they physically resemble mineral lizards is the only clue as to their incipient petrification. Their only distraction is offered by wooden consoles containing copper cords, an archaic and all-powerful version of present-day computers, which allow them to play games, reinvent their lives and memories, and physically metamorphose at will. The exhibition’s title, In Praesentia, which, in the field of rhetoric, refers to a type of metaphor where both elements of the comparison are explicitly mentioned, could be understood in light of the novel’s scenario. Whereas in Garcia’s novel the analogy with our society is hinted at, in Trannois’s exhibition our world and its reconstructed image are co-present and interpenetrate each other. Time has stopped in the villa, freezing the objects and the scattered memories it contains. A nod to Lucio Fontana, a series of mineralized eggs whose enameled surfaces are painted over with a spatial sfumato allow the viewer to escape into the ether, but will never hatch. Their calcification leads to various consequences, as some of the porcelain works are distorted by firing and others are cracked, echoing the syncopated patterns of the balcony railing. These are the risks posed by a dead memory, compared with the healing abilities of a living memory. Although this domestic variation could be connected to transhumanist fantasies about the eternal preservation of minds in silicon chip avatars and servers – the basic material of porcelain – one might rather conclude that Trannois’s work deals with his anxiety regarding his medium, painting. In this field, everything seems to have already happened. It is only possible to recombine and stylize memories into allegories of the loss of meaning. These games, however, are fertile; by refusing to be assigned to a fixed identity, Niels Trannois fictionalizes his memory in order to open it up to collective affects, imbued by the feeling of loss.

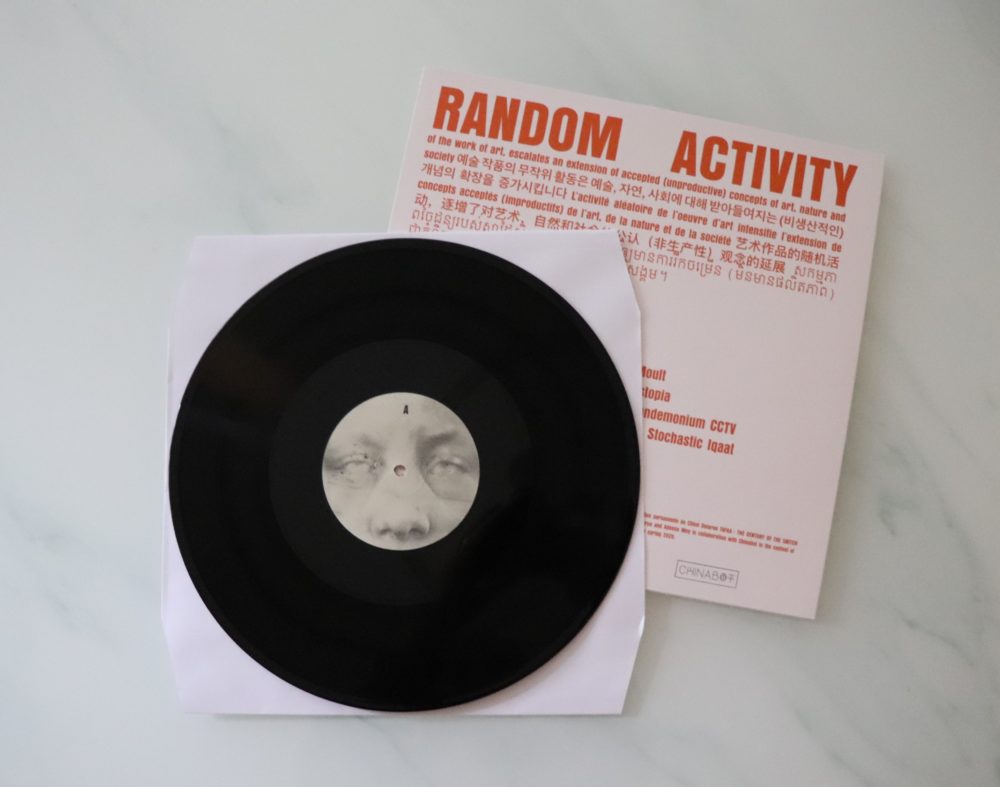

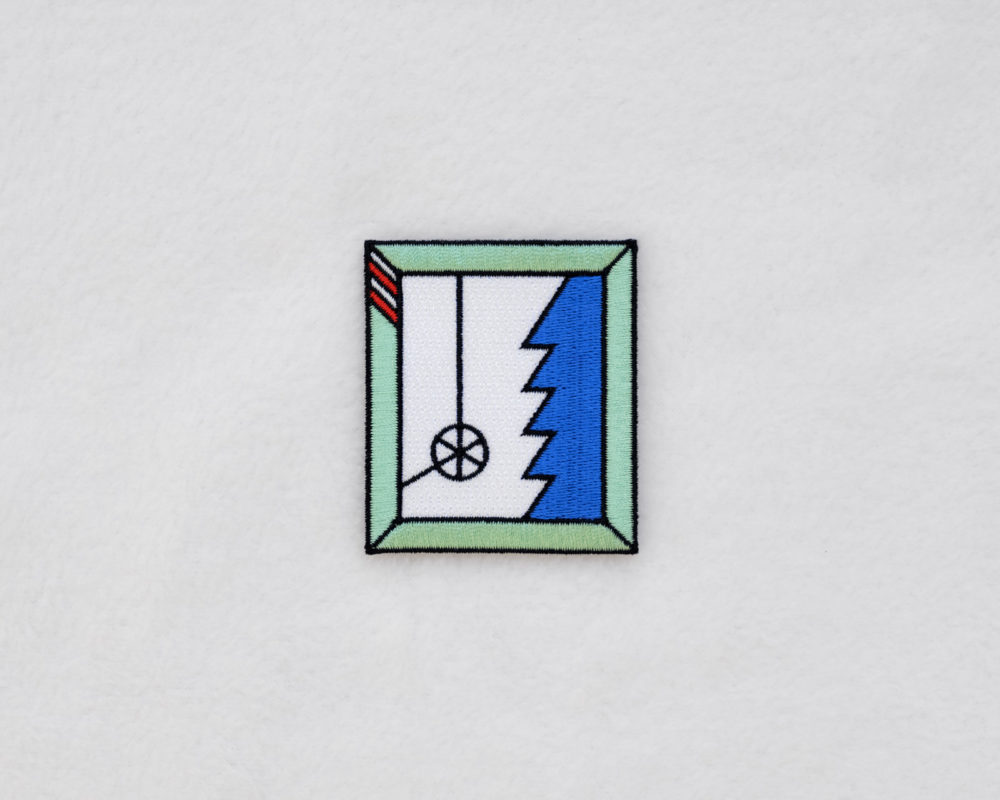

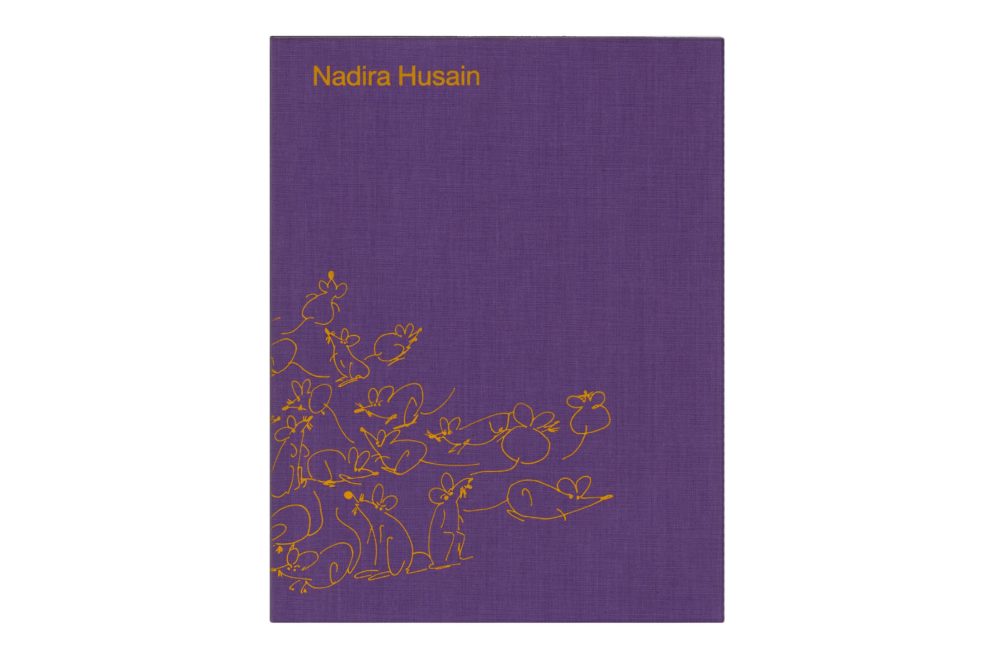

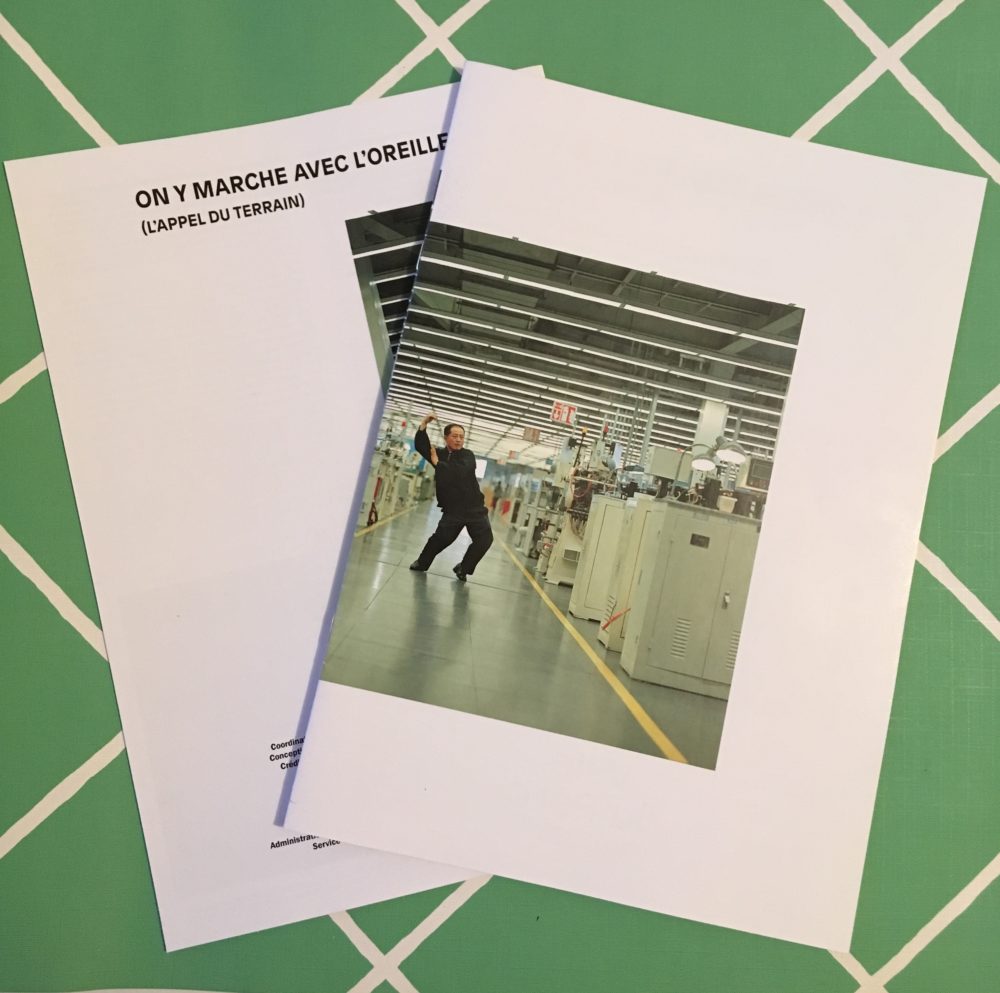

Niels Trannois, In Praesentia, photo by Aurélien Mole

Niels Trannois, In Praesentia, photo by Aurélien Mole

Niels Trannois, In Praesentia, photo by Aurélien Mole

Niels Trannois, In Praesentia, photo by Aurélien Mole

![Le classisme : une introduction [extrait] - Villa du Parc](https://villaduparc.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/mg-3652-livret-72dpi-667x1000.jpg)