More Stories from the Water

Julie Portier

“It sometimes seems that that story is approaching its end. Lest there be no more telling of stories at all, some of us out here in the wild oats, amid the alien corn, think we’d better start telling another one, which maybe people can go on with when the old one’s finished. Maybe. The trouble is, we’ve all let ourselves become part of the killer story, and so we may get finished along with it. Hence it is with a certain feeling of urgency that I seek the nature, subject, words of the other story, the untold one, the life story.”[1]

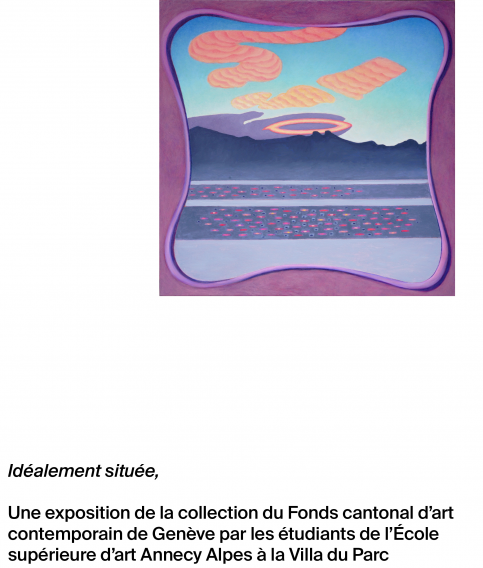

The exhibition of Éric Giraudet de Boudemange at the Villa du Parc takes the form of a parody of a spa which is part of the branding of an imaginary brand of mineral water. This description does not particularly align with the opening quote from a landmark text of eco-feminist thought, especially when the artist is a cis white male with a signet ring on his finger. But I am going to try to make my point with this introduction. As the exhibition is deals with the different stages of existence, I should let the reader know that I met the artist ten years ago, when we were both young. Éric was working on a performance with live pigeons and a pigeon fancier from a working-class background, and was continuing his research on trajectories, what determines them, and what makes them deviate, on the nuance between the goal and on the meaning to attribute to a movement. The article that followed was, of course, humorous. It described forms that were “at once seductive and obscure”, and the artist, in a quote, expressed his taste for all things ambiguous. I concluded with a candid yet frightfully prophetic phrase: “Could this be the place for a reconnection with our natural environment or even our forgotten instincts?”[2]

Telling the story of life is what advertising has been doing since before we were born. We were surrounded by these stories, which, whether promoting an insurance policy, moisturizing cream, ham or bottled water, all had more or less the same flavour. They allowed us to experience ecstasy in the heart of the ordinary (simple things), they celebrated the miracle of perpetuity (for millennia, from mother to daughter). The demonstration of truth through the infinitely small, or the reconstruction of what goes on inside (the stomach, the drum of the washing machine), what Roland Barthes called “advertisements based on psycho-analysis”, “[involving] the consumer in a kind of direct experience of the substance”[3], was – and is – still valid since the 1950s. But it seems that in the 1990s, advertising began to reveal the natural, pure character of things endowed with unsuspected depth, their place in an immutable cycle, the virtuous cycle of life, powerfully connected to the components of the universe (water, air, life). It is of course pointless to denounce the conservative logics at work in the advertising imagery as they seem to be accepted as a kind of folklore by today’s youth – advertising having begun to parody itself even before the television era ended. The evian baby is a good example of this, where the argument for the benefits of water in maintaining the body’s youthfulness has drifted into a paranormal and utterly monstrous phenomenon: the instantaneous transformation of adults into the children they once were. Incidentally, I had never wondered whether the lyricism of this storytelling, making the cyclical movement and normal course of things a guarantee of quality or even a moral value, had any effect on the psyche of my generation. It was around that time that the process of degradation of living conditions on Earth caused by human activity began to feature prominently in the media, as ordinary people became aware that the spiral of productivism was neither virtuous nor eternal.

At that time, young artists from Grenoble had already seized on the new terms and imagery used to talk about climate change in a project called Ozone[4], which also took the form of a marketing operation. In my opinion, the glass entrance of the Villa du Parc, set up as a reception area for the “4Rivières Wellness Space©” signals, from the entrance of the exhibition, a kinship with the corporate fictions that developed in the art of the 1980s, adapting the strategies of institutional critique to the advance of globalized capitalism. This is evident in the goodie stands, glossy leaflets, and standing tables – the ultimate sign of dematerialized exchanges compensated for by mediocre design – but also in the potted ficus tree.[5] I will come back later to the critique of cultural institutions as one of the many possible levels of interpretation of the 4Rivières exhibition. But I must insist on the subversive character of what is presented as a playful, participatory experience.

It should be noted that the identity of the company whose rhetoric is caricatured in the exhibition is not concealed, to the point where the blue and pink colours of its logo are used. The same goes for the fashion house with which it partnered in 2022 to launch a sportswear line supposedly “highlighting their shared commitment to a sustainable future”:[6] the artist even makes a meme out of it in the form of sweatshirts bearing the “Balmian” logo. Combining the fashion industry, recognized as one of the most polluting, with another industry based on the privatization of a common good whose scarcity is a major cause of inequalities throughout the world[7] (drinking water), this greenwashing campaign sparked the ire of environmental defence associations. Furthermore, the agri-food giant Danone, which owns the Alpine mineral water brand, was taken to court in early 2023 by several NGOs for its failure to set a course for phasing out plastic. This bad press is compounded by the recent discovery of non-regulatory levels of pesticide residues (Chlorothalonil) in all water collection areas, including in the French Alps.

The announcement set in motion the APIEM (Association pour la Protection de l’Impluvium de l’Eau Minérale evian, Association for the Protection of the Catchment of Evian Mineral Water). Initiated by the multinational corporation, it involves the surrounding municipalities in monitoring the quality of agricultural soils in the rainwater collection area, a zone that an elaborate communication presents almost as sacred ground. This arrangement, placed under the auspices of concepts such as care, “local”, “sustainable” and “win-win”[8], is as inspiring for the artist as the forms derived from advertising delusions, which grow larger as the values attributed to the product collapse (here, a parallel can already be drawn with art). While all his projects are based on field studies, Éric Giraudet is particularly interested in these complex, critical spaces, where ideals and distant material realities overlap, where opposing stakes and scales acknowledge their interdependence. This requires dealing with language and consciousness, making practical and symbolic adaptations, the manifestations of which the artist observes before re-engaging them in his work through a different form of collage. This was made possible by the residency organized by the Villa du Parc in the Vallée verte, where he forged relationships with farmers practicing energy healing. With them, he shot the film Géobiologies, the cornerstone of the exhibition.

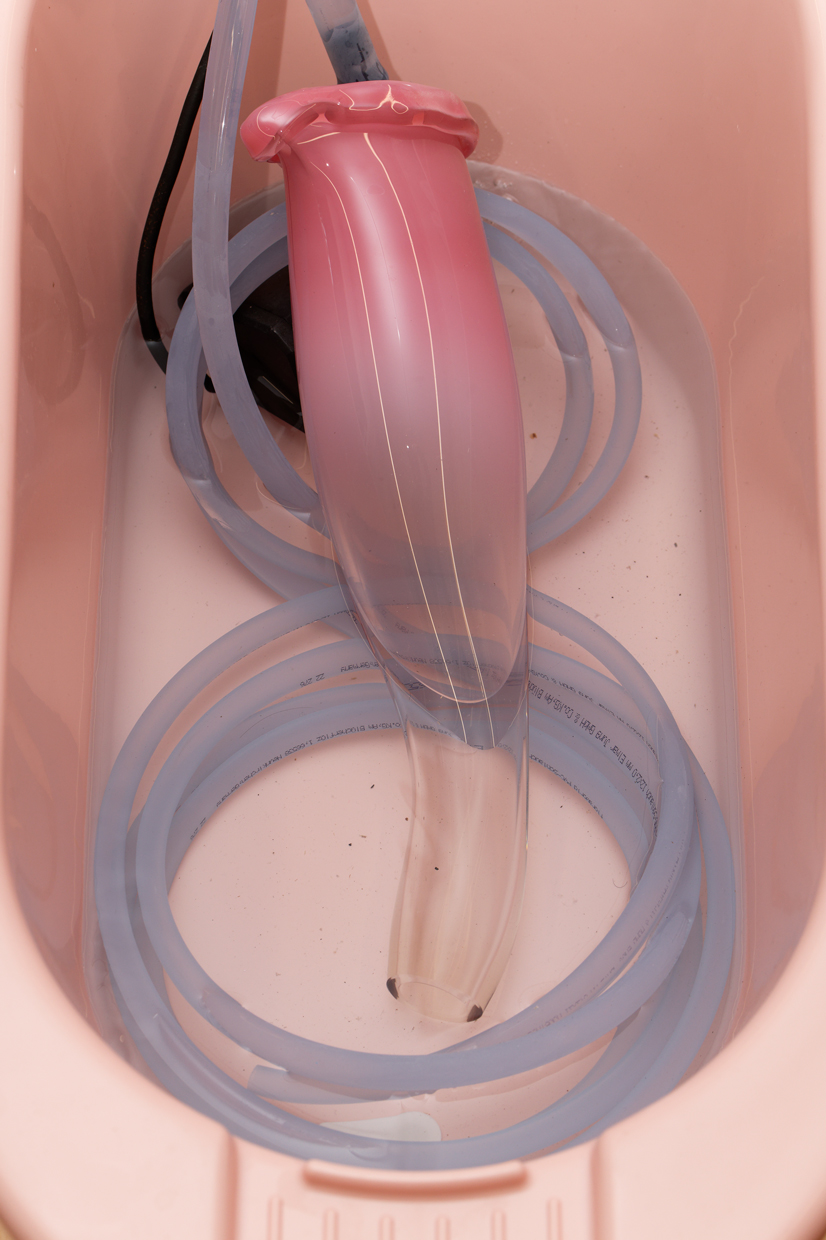

The 4Rivières exhibition, named after a neighbouring community of municipalities that has been transformed into a brand of magnetized water, thus connects the imagery of the marketing world of a natural, luxury-oriented product with that of cosmic, earth-oriented thought and practices. These two worlds share a territory as well as key concepts such as cyclical movement, health, care, the invisible, interiority and purity. At first glance, it takes the form of a decadent spa treatment where visitors are guided from room to room, each offering its own specific sensory experience, ranging from humid warmth (on the first floor) to dry heat (upstairs). In this regard, Éric Giraudet’s exhibition is reminiscent of the sophisticated scenography of spas, which claim to offer “total” relaxation. We are taken on a subcutaneous journey, before being breathlessly propelled through the villa’s corridors to an arid, almost science-fiction-like landscape, where we may have to abandon our corporeal envelope. While this psychedelic scenario employs relatively modest special effects (wallpaper, colored gels and a few water pumps), we are struck by an almost rococo excess, that shifts from enchantment to comic effect, into discomfort. This movement seems to be too well mastered and perverse for it not to contain a critique of the strategies of seduction inherent to the immersive exhibition format.

The artist takes up the advertising parable of the water cycle to alter its purity. It begins with plastic baby bathtubs that transpose the image of the fountain of youth into prosaic reality. The blown-glass sculptures soaking in them seem out of breath, like young parents overwhelmed by childcare tasks. A swollen vulva occasionally emerges from their shapeless mass, threatening to tip the whole thing over. By reintroducing the motif of Eros and Thanatos, the artist undermines this cosmetic reverie. This becomes clear in the film La chanson de la barque de Charon, displayed in the following room, where the combination of image and sound restores a dialectic of life and death. While the image, composed of a montage of advertising clips, illustrates a contemporary myth of the scientifically controlled birth of an infant, the soundtrack plunges this watery, déjà-vu paradise into a morbid mood. It tells the story of a corpse drifting down the river Styx until it reaches the sea, where it eventually revels in its own decomposition. It feels like a hypnosis session aimed at freeing us from the sedative action of crystalline torrents and synthetic moisturizer drops. Meanwhile, the artist’s whispered voice pours out yet more “muddy”, “fishy” and “rotten” images.

I had already noticed how melancholy and the grotesque go hand in hand in Éric Giraudet’s work, which sometimes reminds me of Bruce Nauman, Ugo Rondinone or Paul Mcarthy (to name but a few old men), all of whom have embodied figures of clowns and jesters. There is always something overflowing in Éric Giraudet’s work, something that, aesthetically and morally, we don’t quite know what to make of. It is a quality I have found in precious few French artists. It is especially true when his work addresses existential questions: love, the myth of origins, and notably in his performances. An example of this kind of strange emphasis is the ending of Yvain, a performance given in 2019 at La Criée in Rennes. After live subtitling a video game he created, inspired by a medieval novel about the unsuccessful love affair of a young squire determined to return to the wild, the artist, dressed in a green Lycra suit, donned a plastic chimpanzee mask to recite a slam while awkwardly performing an R&B-style choreography. That time, I wasn’t there to enjoy the atmosphere in the room, but several years earlier, I had seen the artist wearing a horned helmet to guide the audience through the woods while telling a story about a “cuckold”. Riding a stuffed deer’s head, he ended up straddling a pile of raw offal before a pack of hunting dogs was unleashed upon him. Thus ended Hourvari ou le charivari des sentiments at Le Cyclop in Milly la Forêt (2014), in a feeding frenzy in which the artist was metaphorically the prey.

Despite it seeming more restrained, the exhibition in Annemasse also features some unsettling associations, bordering on the obscene, as exemplified by the plaster castings of placentas adorned with a scallop shell. Bearing the initials of the artist’s own daughter, and maybe representing her double, they have all the makings of a memento mori for a newborn baby. Aside from the Polaroids exposing family intimacy, it is through this small, rough texture, contrasting with the vibrant aspect of the exhibition, that the artist signals the introspective nature of what is being portrayed here. Finally, the forced juxtapositions that constitute the artist’s method of investigation – in this case, linking evian’s marketing campaigns with esoteric practices in rural settings, all set against the backdrop of the climate crisis – give rise to monstrous formulations that could also be seen as the ordinary syntax of a confused era. Such is the case with the spermatozoa penetrating the epidermis in the falsely didactic installation in the corridor, but even more so with the analogy of fluids between the two floors of the art centre, from one film to the other, cleverly arranged along a vertical axis. The virginal water and fantastically propelled breast milk on the ground floor seem to trickle upstairs in the form of slender, turbid jets in Géobiologies, his film, where the liquid transforms alternatively into cow’s milk and urine, ultimately producing the bitter image of a closed circuit.

What both films have in common is that they link the idea of water to nature, and more specifically to an Alpine landscape, which appears in the opening shot of Géobiologies, looking like an advertisement image. Could the photogenic allure of this environment encourage interest in the invisible world it contains? It could be a way of updating the question of the sublime in the era of communication. Géobiologies does not directly answer this. True to the strategy of product placement, the video logically promotes the magnetized water available at the entrance, and spectators are offered a tasting at the start of their visit. The sleek, futuristic design of the 4Rivières© bottle, which turns out to be a carafe and not a sealed bottle, appears in the video in various situations, as a unifying, multi-purpose product (characteristic of a miraculous preparation): for humans and animals to drink, for cheese-making, for washing feet… The video employs a tactic familiar in advertising storytelling: integrating a new product into an ancient tradition, even if the packaging stands out too much in the setting. However, when the 4Rivières© water bottle is consumed by a farmer or poured into a fermentation vat, it serves as a bridge between reality and fiction, in an almost didactic way. We literally witness the dilution of fiction into reality – something that could also be considered a miracle – a reality depicted in a stripped-down, sometimes crude image, framed in a stable, a muddy pasture or at a Reblochon cheese factory. Bodies are filmed without embellishment; skins are sometimes reddened and damaged by work, far from the “hydrated from the inside” epidermis promised by the luxury mineral water. For me, the actors in Géobiologies become the icons of a proletarian water, flowing down the laborious and perhaps rebellious side of the mountain.

Here is an alternative story: a story that seeks out its characters in the margins or in the background, characters who do not have the characteristic traits of heroes or conquerors, whose actions unfold in the longer time frame of everyday life, dedicated to caring for their environment rather than reshaping it by force. To return to the other story Ursula K. Le Guin called for, which would be the other (non-dominant) stories told in a plural voice, would require changing methods to write them. Éric Giraudet’s method, as I have said, consists in approaching a territory and identifying its contemporary issues, before reformulating them through a group gathered by a minor or devalued practice, or one linked to folklore. The resulting film and his other works are based on the hypothesis that this practice could have an allegorical significance in a given context. This is exemplified by fierljeppen, the pole-vaulting sport practiced over the canals in the Netherlands, which the artist had begun to follow at the time of our meeting. Placed in the context of rising sea levels and intensified land use, and within a history of planarity in painting, this vernacular sport appears as a poetic gesture of resistance.[9] Formally, this may lead to revisiting the camera angle (in the earliest fierljeppen images, the camera was attached to the runners’ poles), loosening genre categories (fiction, documentary, parody, ethnographic survey all at once), but most importantly rethinking the role of the subject who, in most of Éric Giraudet’s projects, becomes an actor: interpreting their own role and habitual gestures, more or less modified by the script. In the early 2010s, other artists of the same generation, such as Bertille Bak, Eléonore Saintagnan and Mohamed Bourouissa, who also studied at Le Fresnoy, and about whom I have also had the opportunity to write, developed specific processes of participation with the filmed subjects. While it may have been encouraged by residency programs – which are certainly worthy of criticism[10] – aimed at promoting “territories”, they have nonetheless opened up new avenues for an art concerned with reality and committed to making visible, or giving a voice to, those who are less heard and seen. A way of writing other stories with their protagonists.

In Éric Giraudet’s work, these alternative stories, while affirming their connection to reality, ironically slide into the B-movie genre. This is evident in Géobiologies, which gives a fairly faithful account of the worldview embraced by the protagonists: a system of connected fluids and energies, contributing to the symbiotic functioning of the various earthly species. This approach largely coincides with the revival of contemporary biology and social science, which is also more inclined to consider spiritualities when developing theories. In this regard, the practices of the Alpine healers are a perfectly valid allegory for the present day. However, it is recounted through references to fantasy films and thriller series, using crude devices which, as is often the case with the artist, border on self-mockery. For example, there is an electrical crackling that recurs in the soundtrack every time a liquid made of water appears, as if to signal paranormal activity, or the exaggerated transitions from one shot to the next, which lend a paranoid feeling to the idea that everything is connected in a grand whole.

It would be wrong to see the use of parody as disdainful. Rather, we might recognize it as evidence of the artist’s charisma, that is strong enough to gain the trust of farmers and allow for a measure of detachment. The artist has had several opportunities to express his interest in spirituality within counter-culture. In 2016, he spent several months in a residency in Louisiana with a Cajun healer. Drawing from this experience, he developed a series of actions combining practices and references with a high level of syncretism and, again, a dose of humour. The performance invited participants to “create new narratives”, meaning examining things from the other side of colonial history and segregation. The artist considered his performances as rituals long before he met with shamans, giving them a symbolic function involving issues of reconciliation or improvement of living together from the onset. But it is worth noting that the figure of the guru is always evaded through humour: the artist plays the role of a slightly borderline ringmaster, grappling with heartaches and existential doubts.

However, I could not ignore the critical function of this work, as I find it so refreshing in contemporary art and cultural institutions, where the vocabulary of care has been particularly instrumentalized. In this regard, proposing contradictory versions of this notion in the depiction of a wellness centre in lieu of an art centre is ironically relevant. It is also a context in which the resurgence of New Age spiritualities and the promotion of positive thinking have become commonplace, presenting themselves as antidotes to any political or social subject that might be more discomforting. On the contrary, art that encourages a reconnection with the living often facilitates relations with the public and with certain policies, especially when they are aligned with earth-oriented values and convinced that art should offer more than just art. Therefore, I assume that the spa metaphor and the participatory experience ironically promoted in the exhibition, while in practice limited to being offered a glass of water on entering, serve as a commentary on the increasingly pressing expectations placed on art. On this matter, the artist has often used the motif of play in his exhibitions, not so much to provide entertainment as to engage the audience in an active relationship with the artworks. What does it mean, then, to shift from the figure of the player to that of the spa customer, who can be seen as the epitome of passivity? I think that, for this new forty-year-old father, it is a nod to the passage of time, often synonymous with weariness and the adoption of middle-class views. But it also reflects the shift from a “leisure society” to a “society centred on well-being”, which does nothing to remedy the general state of confusion in which art is constantly having to justify itself.

All of this seems to affect the silicone figures found lying, deflated and decompensating in the warm rooms of the 4Rivières© spa. Casts of the artist’s body have been appearing since his earliest exhibitions, initially through the motif of the hand, identifiable by the family signet ring. Mounted on a pole, they form a jester’s sceptre, as found in the first room, left in the checkroom next to a bathrobe. In this way, the figure of the artist intervenes in the sculptural work as a dismembered mascot and, with his “molts”, as a clownish, flayed figure. With all the ambivalence cherished by the artist, these signs are at once an admission of narcissism, a certain sentimentality and, I believe, a way of taking on the responsibility of authorship, as all signatures are meant to do. But the molts, elsewhere adorned with artificial flowers or petrified in bas-reliefs, have a strong connection with the sense of finitude and, more particularly here, with obsolescence. In the desert-like impluvium staged in the grand salon on the upper floor of the Villa, not without reference to the exploitation of Boudemange’s land, one of the molts is crammed into a bucket. As though it has been thrown in the garbage, it stares at us, pitiful, with stuffed animal eyes. Beyond the aristocratic lineage or the perpetuation of intensive agriculture and even patriarchy, it is masculinity itself that is struck with obsolescence here. This is rarely formulated in an introspective mode, except by boomers who see a threat in feminism. To conclude, this is what I find the most exciting in Éric Giraudet’s project at the Villa du Parc, and the most daring in the face of the celebration of motherhood that tends to resurface with its share of moralism with the natural-cosmic turn in contemporary art: it is a (complex and critical) story of life, from the perspective of fatherhood.

***

[1] Ursula K. Le Guin, The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction, Ignota, 2019, p. 33

[2] Julie Portier, “Éric Giraudet de Boudemange : Terrains de jeux”, Le Quotidien de l’art, 533, January 31st, 2014

[3] Roland Barthes, Mythologies, The Noonday Press, New York, 1971, p. 36

[4] Dominique Gonzalez Foerster, Bernard Joisten, Pierre Joseph and Philippe Parreno between 1988 and 1990

[5] Famous artist from the Les readymades appartiennent à tout le monde© agency (founded by Philippe Thomas in 1987), an offspring of Marcel Broodthaers’ Musée d’art Moderne – département des Aigles (1968 – 1972).

[6] https://fr.balmain.com/fr/experience/balmain-x-evian, visited on December 5th, 2023

[7] For example, Mexican artist Minerva Cuevas transformed the Alpine brand’s labels to write the word “Equality” in a 2004 installation.

[8] https://apieme-evian.com/qui-sommes-nous/, visited on December 5th, 2023

[9] See the film Friesche Lusthof (2017) and the exhibition The Story of water, Milk & Peewitt eggs at the Fries Museum Leeuwarden (2017).

[10] When they are politically motivated rather than artistic or heritage-related, or when the grant for in situ work is conditional on the completion of a commission.

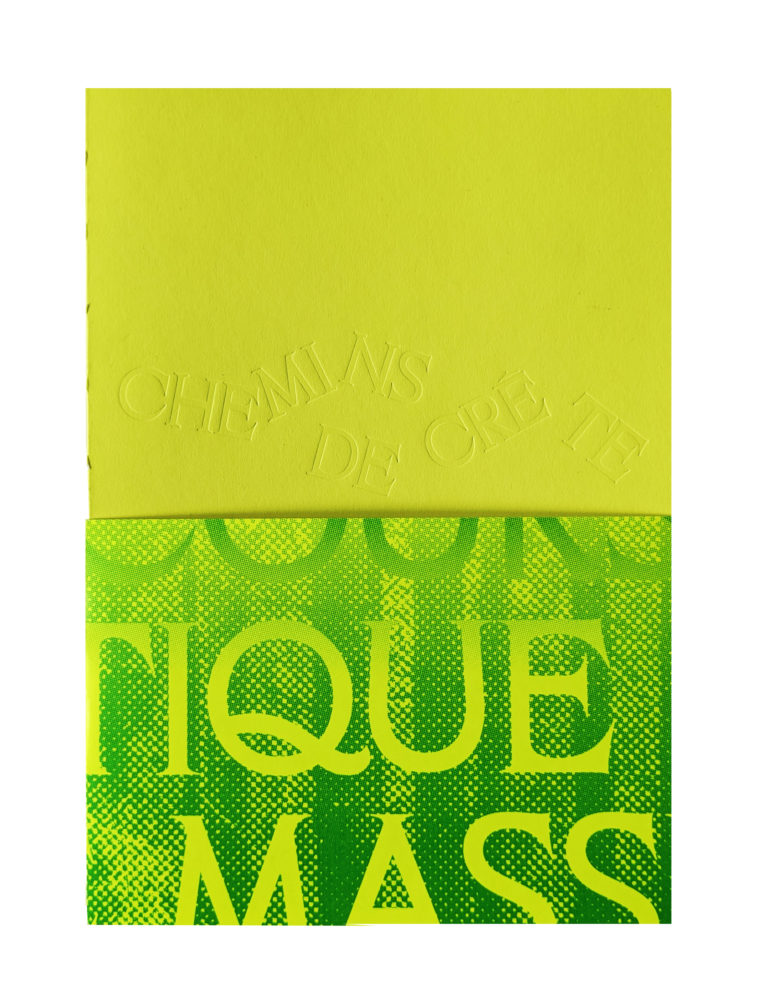

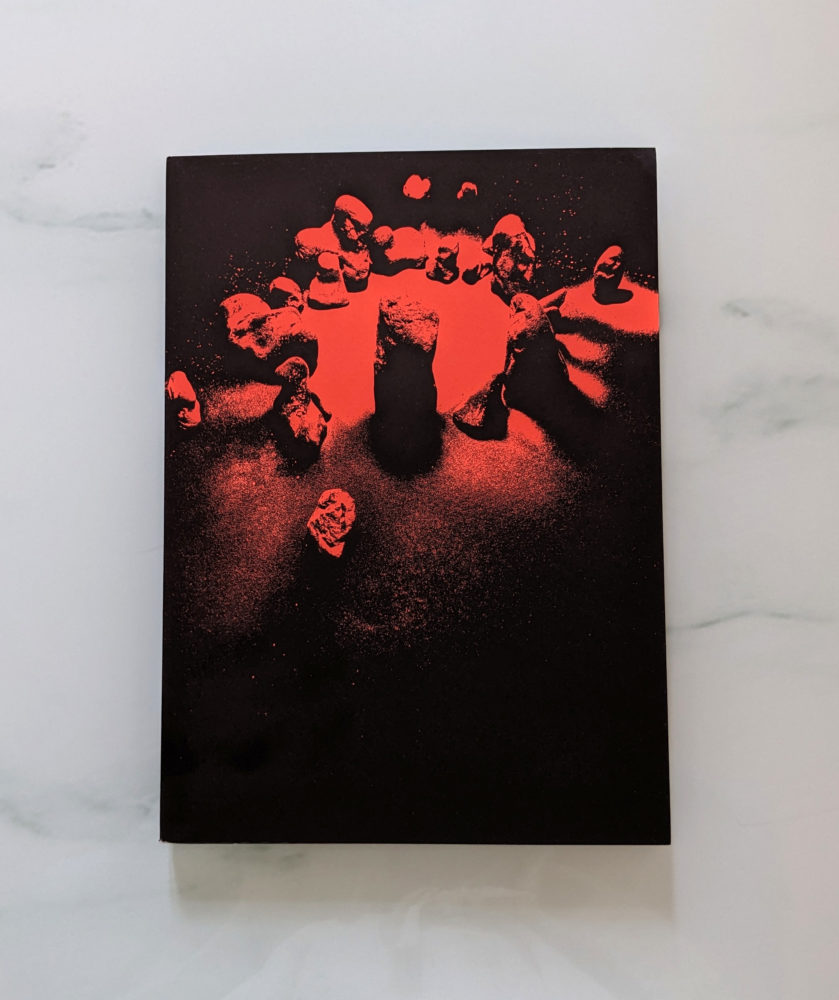

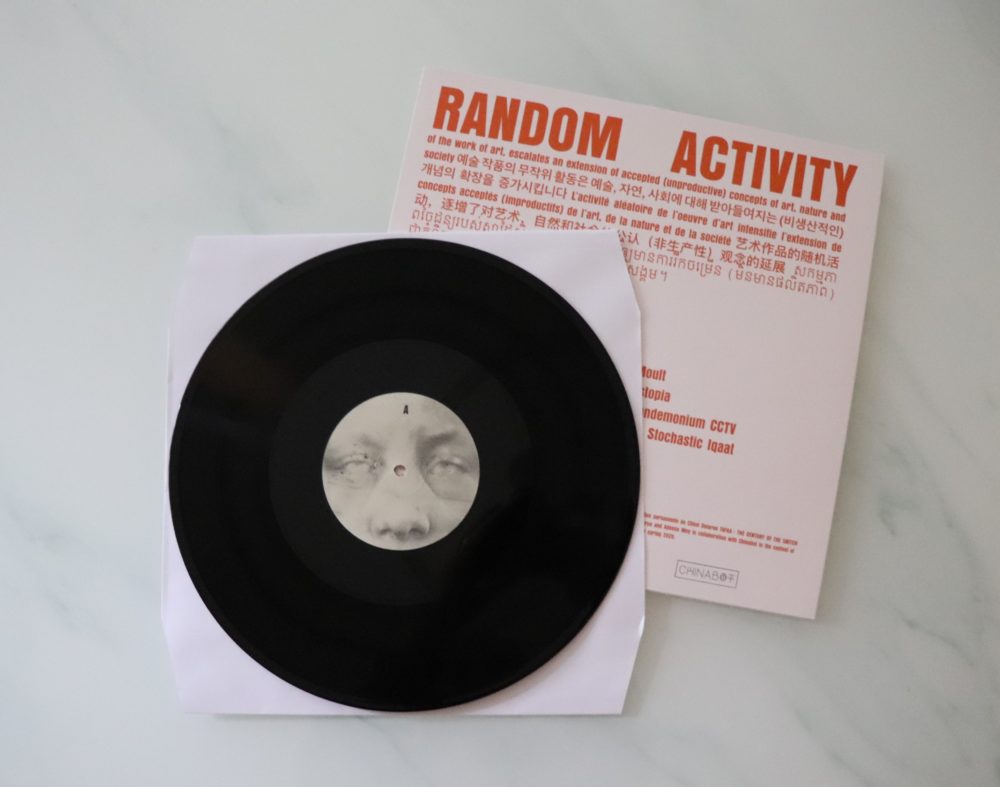

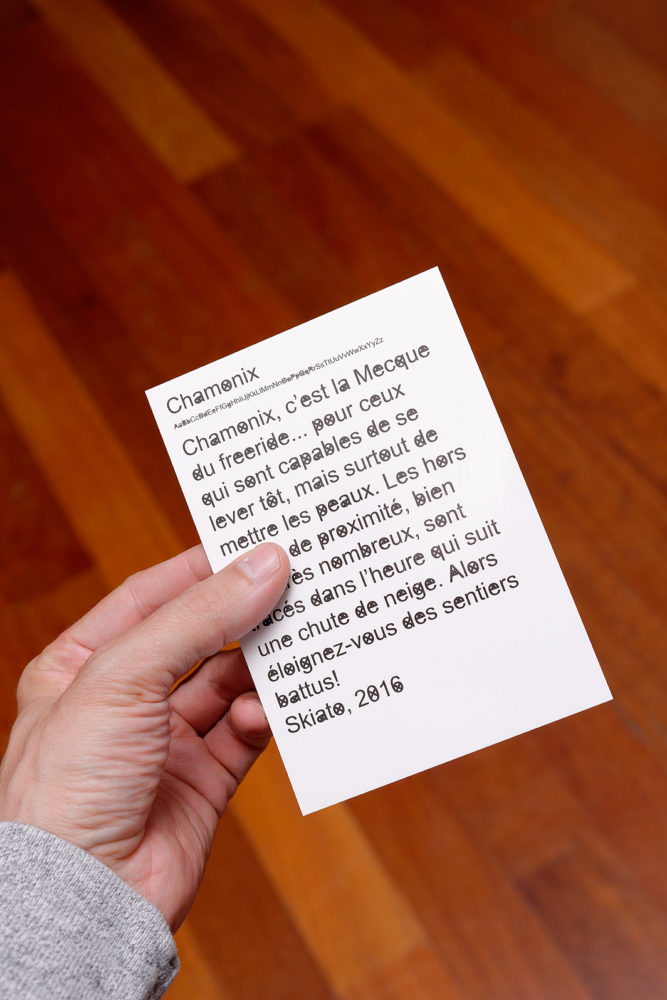

“4 rivières” une exposition d’Eric Giraudet de Boudemange, 2023, crédit photo: Aurélien Mole

“4 rivières” une exposition d’Eric Giraudet de Boudemange, 2023, crédit photo: Aurélien Mole

“4 rivières” une exposition d’Eric Giraudet de Boudemange, 2023, crédit photo: Aurélien Mole

“4 rivières” une exposition d’Eric Giraudet de Boudemange, 2023, crédit photo: Aurélien Mole

“4 rivières” une exposition d’Eric Giraudet de Boudemange, 2023, crédit photo: Aurélien Mole

“4 rivières” une exposition d’Eric Giraudet de Boudemange, 2023, crédit photo: Aurélien Mole

“4 rivières” une exposition d’Eric Giraudet de Boudemange, 2023, crédit photo: Aurélien Mole

“4 rivières” une exposition d’Eric Giraudet de Boudemange, 2023, crédit photo: Aurélien Mole

![Le classisme : une introduction [extrait] - Villa du Parc](https://villaduparc.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/mg-3652-livret-72dpi-667x1000.jpg)