CASABLANCAS

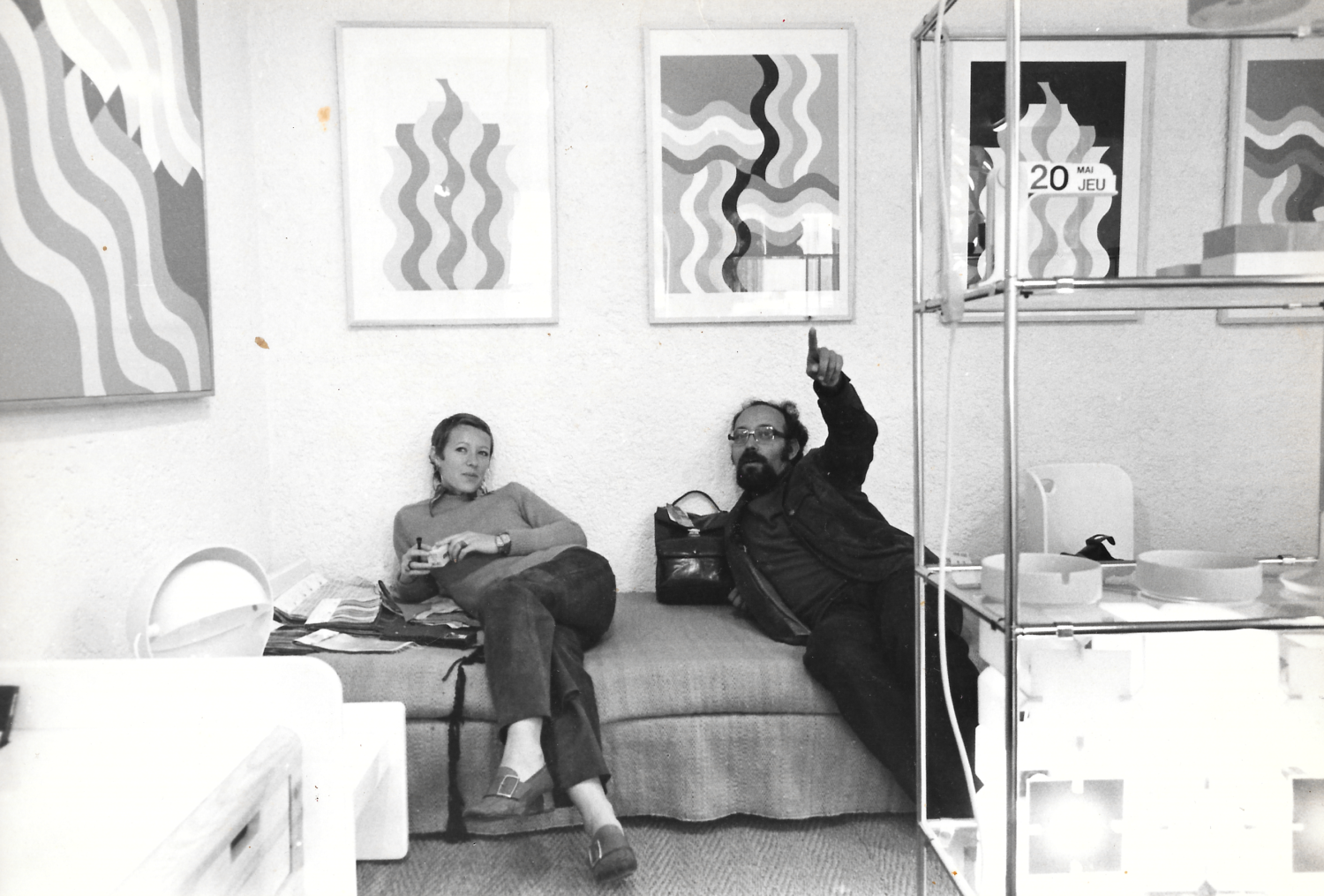

Ninon Lesourd and Mohamed Melehi at the gallery L’atelier, Rabat, 1971. Archives: Pauline de Mazières.

Gabrielle Camuset has invited Maud Houssais to show her latest work in La Villa du Parc’s porch exhibition space. Exhibiting the CASABLANCAS archives is part of a lively group movement fueled by different researchers, curators, artists, independent art venues, and official institutions to showcase the experiments in artistic modernity in Morocco. We might mention in this regard a forthcoming publication devoted to the archives of the school of fine arts in Casablanca, edited by Maud Houssais and Fatima-Zahra Lakrissa, and published by Zaman Books & Curating, or School of Casablanca, a group project involving residencies, public programs, and online archives headed by the KW Institute for Contemporary Art and the Sharjah Art Foundation, in collaboration with the Goethe Institut Maroc, ThinkArt, and Zamân Books & Curating.

CASABLANCAS

The 1960s and ‘70s in Morocco crystalized the beginnings of a reflection on town planning in which the philosophy of the city went hand in hand with art initiatives in the urban space. The newly formed art and cultural social circles following independence took this question as their own to form a collective project of social, political, and cultural reform. In this regard, Mostafa Nissaboury, the poet and cofounder of the cultural reviews Souffles (1966-1971) and Integral (1971-1977) – offers readers in his text titled “Casablanca, fragments d’une mémoire dispersée” a retrospective narrative that lies midway between an eyewitness account and a study carried out in the field, focusing on what Casablanca symbolized in the 1970s. Namely, the city was the embodiment of a field of struggle in terms of both a social struggle and ideas generally, in a sensational questioning of norms and the dictated frameworks for reflection and thinking. Nissaboury deploys in his text ways of writing and pinning down collective memories which can only be thought and articulated by wandering through the physical space – the streets – and symbolic space – memory and history – of the city.

The CASABLANCAS archives show imagines the visual counterpart to a walk through Casablanca in the 1960s and ‘70s with a scattered though augmented memory, drawing on the archive and documents to summon art practices that helped to produce the city. The invention of a new visual culture is a crucial element in working out the project of a society that must also take place through images. In this regard then, Casablanca’s School of Fine Arts, headed by Farid Belkahia from 1961 to 1974, constituted a fertile ground for an urbanistic conception that sees the artist as a fully-fledged influencer. Display in public spaces, graphic design, interior and urban planning and development, and social photography become the touchstone of a decolonial committed art within society. Cinema embodies the catalyst of popular urban culture, which it helps to both found and fix in place. By way of an example, there is Ahmed Bouanani’s short film 6 et 12, which features Casablanca between 6 am and noon. Finally, the graphic and applied arts agencies founded by artists, like SHOOF, which was opened by Mohamed Melehi and Studio 400, opened by Mohammed Chabâa, or those that worked closely with artists, like the Faraoui and de Mazières architectural firm, stand as a fundamental contribution to the output of a visual culture applied to the street and the city as a whole.